Bombshell: Spoofing The Image

After the triumph of Dinner At Eight, Jean Harlow reunited with the team that gave us Red Dust and produced the most madcap comedy of her career, a satire of Hollywood and celebrity that hit very close to home as it turned out.

After the triumph of Dinner At Eight, Jean Harlow reunited with the team that gave us Red Dust and produced the most madcap comedy of her career, a satire of Hollywood and celebrity that hit very close to home as it turned out.Based on an unproduced stageplay, Bombshell was initially conceived as a tragedy based on the wild up-and-down career of "It Girl" Clara Bow, but when screenwriter John Lee Mahin (Scarface, Red Dust) suggested the story would work better as a comedy, director Victor Fleming immediately seized on the idea.

"She used to be my girl," Fleming explained. "You'd go to her house, and there'd be a beautiful Oriental rug with coffee stains and dog shit all over the floor and her father would come in drunk, and her secretary was stealing from her."

"She used to be my girl," Fleming explained. "You'd go to her house, and there'd be a beautiful Oriental rug with coffee stains and dog shit all over the floor and her father would come in drunk, and her secretary was stealing from her."Instead, Fleming and Mahin set out to do for Hollywood what The Front Page did for newspapers—turn a secret society inside out and show it, in the words of associate producer Hunt Stromberg, as "a crazy house, a burning Rome, a very miserable place."

"Gee, what a business," Harlow exclaims, "you might as well run a milk route!"

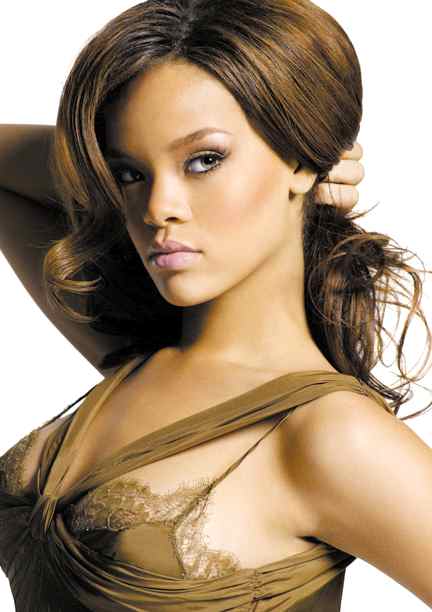

As produced, Bombshell (also known in some parts of the world as Blonde Bombshell) is the story of "If Girl" Lola Burns, a voluptuous, platinum-haired beauty with a film career virtually identical to Harlow's own, with a montage of clips from her movies and personal appearances substituting for Lola's—there's even an explicit reference to the rain barrel scene from Red Dust. Worked like a plow horse and played for a sucker, Lola wants love and respect but has no idea how to get either, and she bounces from one empty source of affection to the next, be it a phony aristocrat, an adopted child or an East coast blueblood (Franchot Tone) who woos her with lines such as "Your hair is like a field of silver daisies. I'd like to run barefoot through your hair!"

As produced, Bombshell (also known in some parts of the world as Blonde Bombshell) is the story of "If Girl" Lola Burns, a voluptuous, platinum-haired beauty with a film career virtually identical to Harlow's own, with a montage of clips from her movies and personal appearances substituting for Lola's—there's even an explicit reference to the rain barrel scene from Red Dust. Worked like a plow horse and played for a sucker, Lola wants love and respect but has no idea how to get either, and she bounces from one empty source of affection to the next, be it a phony aristocrat, an adopted child or an East coast blueblood (Franchot Tone) who woos her with lines such as "Your hair is like a field of silver daisies. I'd like to run barefoot through your hair!" The one guy who really does love and respect her is, of course, the one guy who won't tell her and the two spar and bicker and feud their way through the whole movie, which is the rom-com code for sexual attraction. (In this case, Lee Tracy plays the love interest, "Space" Hanlon, as more of a manipulative jerk than a tough-talking Romeo and proves to be the movie's weak link. Oh, what Clark Gable could have done with this role!)

The one guy who really does love and respect her is, of course, the one guy who won't tell her and the two spar and bicker and feud their way through the whole movie, which is the rom-com code for sexual attraction. (In this case, Lee Tracy plays the love interest, "Space" Hanlon, as more of a manipulative jerk than a tough-talking Romeo and proves to be the movie's weak link. Oh, what Clark Gable could have done with this role!)The movie skewers every Hollywood type—the hangers-on, the rapacious press, the stalkers, the slicky boys, the fraudsters, the petty tyrants—and does so with a manic quality that would characterize the screwball comedies allegedly invented by Howard Hawks and Frank Capra in 1934, but which, as I mentioned in my review of Design For Living, seems to have developed full-blown sometime earlier. Fleming spared no one, including himself—he's caricatured as director Jim Brogan (Pat O'Brien), alternately described in the movie as a "piano mover" and "a smooth-tongued bluebeard."

If the movie as a whole is not on the same level as Red Dust, Dinner At Eight or Libeled Lady (which came later), don't blame Harlow. She's confident and self-assured at the center of this maelstrom and her comedic sensibilities are, as Fleming biographer Michael Sragow put it, "as jiggly as her braless, corset-free look." Contemporary critics such as Richard Watts, Jr. of the New York Herald Tribune hailed Bombshell as "the first full-length portrait of this amazing young woman's increasingly impressive acting talent."

If the movie as a whole is not on the same level as Red Dust, Dinner At Eight or Libeled Lady (which came later), don't blame Harlow. She's confident and self-assured at the center of this maelstrom and her comedic sensibilities are, as Fleming biographer Michael Sragow put it, "as jiggly as her braless, corset-free look." Contemporary critics such as Richard Watts, Jr. of the New York Herald Tribune hailed Bombshell as "the first full-length portrait of this amazing young woman's increasingly impressive acting talent." Although Clara Bow may have inspired Bomb- shell, there was no doubt in the public's mind that the story was a thinly-disguised portrait of Harlow herself—and not just because Lola wore tight fitting gowns and lived in an all-white art Deco mansion modeled on Harlow's own—for though she was now in full command of her onscreen persona, Harlow's off-screen life was a well-publicized mess.

Although Clara Bow may have inspired Bomb- shell, there was no doubt in the public's mind that the story was a thinly-disguised portrait of Harlow herself—and not just because Lola wore tight fitting gowns and lived in an all-white art Deco mansion modeled on Harlow's own—for though she was now in full command of her onscreen persona, Harlow's off-screen life was a well-publicized mess.As they often do, Harlow's problems began at home with an overbearing, controlling mother, Jean Poe Carpenter, nee Harlow, who felt she'd been sold into a loveless marriage by her overbearing, controlling father. After years of resentment and thwarted dreams of movie stardom, Carpenter—"Mother Jean" as she came to be known—finally escaped Kansas City, divorcing her husband and moving to Hollywood with her daughter in 1922.

Mother and daughter lived in California for two years, but Mother Jean's dreams of movie stardom didn't pan out and the pair moved to Chicago; when her mother remarried, Harlow eloped with the brother of a school friend and returned to Los Angeles. She was just sixteen years old.

Harlow divorced her childhood husband three years later and married Paul Bern, a small-time movie director whom writer Anita Loos later characterized as a "German psycho." While Harlow was filming Red Dust, Bern was found dead in the couple's Hollywood home and foul play was suspected until an MGM publicist turned up with a timely suicide note and stories of Bern's emotional problems, summed up by Groucho Marx with the quip, "The fellow who married her was impotent and he killed himself. I would have done the same thing."

Harlow divorced her childhood husband three years later and married Paul Bern, a small-time movie director whom writer Anita Loos later characterized as a "German psycho." While Harlow was filming Red Dust, Bern was found dead in the couple's Hollywood home and foul play was suspected until an MGM publicist turned up with a timely suicide note and stories of Bern's emotional problems, summed up by Groucho Marx with the quip, "The fellow who married her was impotent and he killed himself. I would have done the same thing."The public rallied around Harlow and the box office success of Red Dust guaranteed continued studio support.

That a scandal of such proportions could be so easily smoothed over may be hard to believe for those who have grown up with cellphone cameras, twitter and the 24/7 gossip machine, but in those days, Hollywood could cover up practically anything—murder, rape, pedophilia—and did when the star in question was bankable enough.

Too, because Harlow came across on the screen as a sympathetic underdog who succeeded despite the scandalous behavior of her characters, audiences were willing to give the real-life Harlow the benefit of the doubt—something to think about as you wonder why Lindsay Lohan's antics have ended her career while Charlie Sheen's have only enhanced his.

Too, because Harlow came across on the screen as a sympathetic underdog who succeeded despite the scandalous behavior of her characters, audiences were willing to give the real-life Harlow the benefit of the doubt—something to think about as you wonder why Lindsay Lohan's antics have ended her career while Charlie Sheen's have only enhanced his.Even so, Harlow had to dodge one more scandal around the time of Bombshell's release, this one concerning her affair with married boxer Max Baer. When Baer's wife threatened to name Harlow in the subsequent divorce proceedings, the studio quickly married their star off to cinematographer Harold Rosson (best known for photographing The Wizard Of Oz). The marriage was quietly dissolved seven months later but by then the potential scandal had been headed off. Jean Harlow's career, and MGM's cash cow, was safe once again.

Trivia: MGM may have worked overtime to cover up Harlow's indiscretions, but co-star

Lee Tracy was not so lucky. While filming Viva Villa in Mexico in 1934 with Wallace Beery, Tracy got drunk, stepped out onto his hotel balcony and urinated on a passing military parade. He was arrested on the spot and immediately deported, and a furious Louis B. Mayer fired him shortly thereafter. Tracy's career hit the skids after that, with a lot of small roles in B-pictures, followed by television in the 1950s. He achieved a level of redemption, however, in 1964 when his portrayal of a dying U.S. president in the Henry Fonda movie The Best Man earned him an Oscar nomination for best supporting actor—which is one more Oscar nomination than Jean Harlow ever got. Tracy died of cancer four years later at the age of 70.

Lee Tracy was not so lucky. While filming Viva Villa in Mexico in 1934 with Wallace Beery, Tracy got drunk, stepped out onto his hotel balcony and urinated on a passing military parade. He was arrested on the spot and immediately deported, and a furious Louis B. Mayer fired him shortly thereafter. Tracy's career hit the skids after that, with a lot of small roles in B-pictures, followed by television in the 1950s. He achieved a level of redemption, however, in 1964 when his portrayal of a dying U.S. president in the Henry Fonda movie The Best Man earned him an Oscar nomination for best supporting actor—which is one more Oscar nomination than Jean Harlow ever got. Tracy died of cancer four years later at the age of 70.[To Read Part Four of this essay, click here.]